Braillic’s AR tech helps brain surgeons see through the walls

The medical software provider plans to expand its use to spinal and orthopaedic procedures.

Hong Kong startup Braillic seeks to revolutionise surgical practice through augmented reality (AR) technology, allowing surgeons to precisely locate areas in the brain without cracking the skull open.

It enhances surgical safety, precision, and efficiency, whilst freeing doctors from medical malpractice lawsuits due to surgical errors such as incorrect incisions, which can be catastrophic.

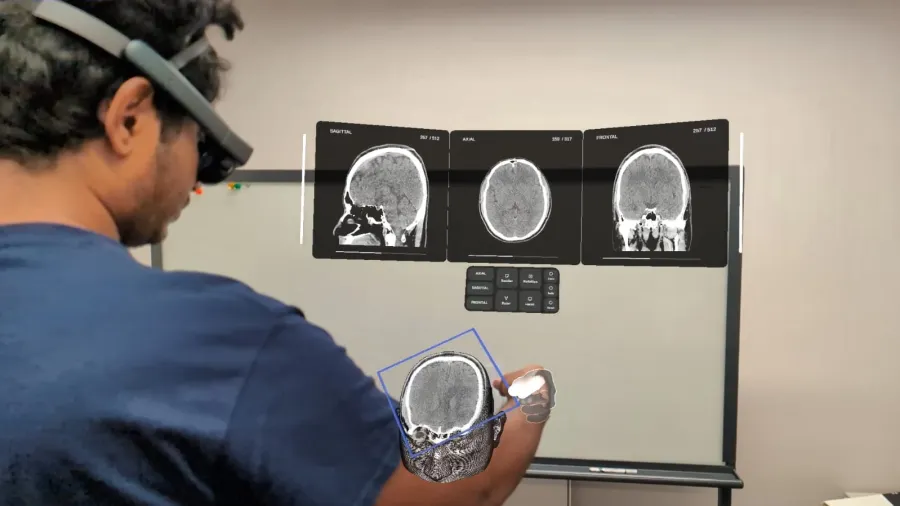

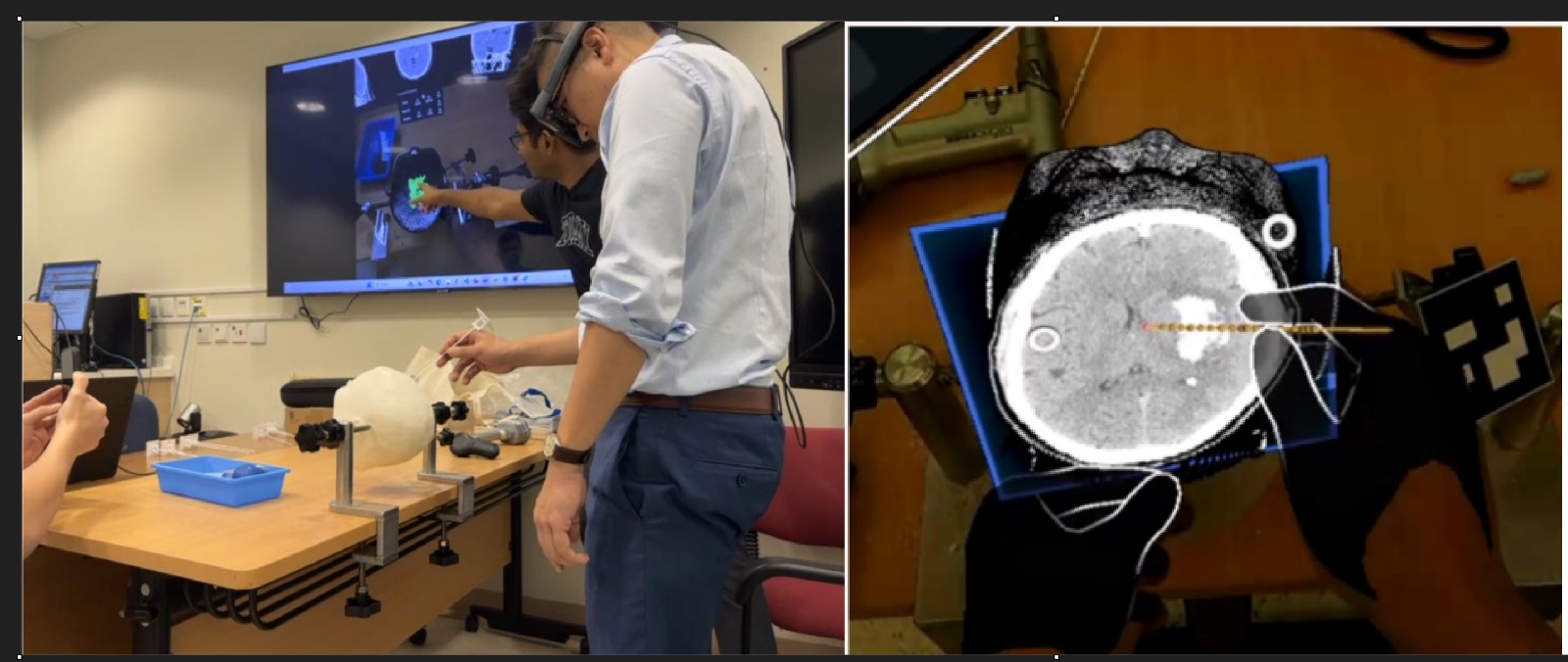

With Braillic’s Augmented Reality Guided Surgical Navigation (ArNav), surgeons gain a clear view of the surgical area in holographic 3D, minimising the need for large openings in the skull. ArNav's accuracy range of five to seven millimetres lets them perform neurosurgery with greater precision.

ArNav is currently used in neurosurgery, but Camroo Ahmed, CEO at Braillic Ltd, told Hong Kong Business he wants to extend its application to spinal and orthopaedic procedures, such as knee and hip replacements, where precise alignment is critical.

Within neurosurgery, Ahmed said their AR tool could be used in ventriculostomy procedures, which involve inserting a catheter into the brain's ventricles to drain cerebrospinal fluid or monitor intracranial pressure.

Ahmed, an electric engineer, said Braillic will apply for a certification from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) so it could expand the technology. He also plans to develop a training platform for surgeons and introduce an artificial intelligence (AI) agent in operating rooms once the company secures US$1m in funding.

To date, the medical AR software startup has raised $1m through private angel investment.

“The Hong Kong government is pretty much putting emphasis on the advancement of medical training because there have been quite a few recent errors in the hospital sector,” Ahmed said. “We have been working with medical professionals on how we can integrate augmented reality not only as a surgical tool but also as a training platform for residents.”

Ahmed said he wants to create an AI agent to help surgeons, especially the new ones, in the decision-making process. “Of course, they are well trained, but we are human, we have doubts. We will always make mistakes. Combining an AI agent with augmented reality will help them validate their decisions,” he added.

Braillic’s team seeks to spur a shift in the medical industry, noting that ArNav is an “alternative and cheaper’ solution.

“Medical technologies are extremely expensive, especially for surgeries,” he said. “In Hong Kong or in the US, they can afford it, but in my home country, Bangladesh or other developing economies, nobody is going to spend a few million to buy a machine to do surgical tracking.”

Ahmed said a typical neuronavigation system, which helps surgeons during surgery, costs several millions, plus maintenance and associated fees. ArNav, on the other hand, will cost $3,000 to $5,000 per use.

“We plan to charge per surgery,” he said. “If they perform a certain number of surgeries, they just pay per use. This is much cheaper than committing to an expensive hardware purchase.”

Ahmed said Braillic’s technology does not replace surgeons but is meant to boost their confidence in the operating room. A surgeon’s judgment improves when he sees what he is working on, he pointed out.

“But usually, they can't see everything — that's where we come in, to help them see the unseen,” he said. “We’re trying to enhance their capacity and boost their confidence with an X-ray-like vision, so they know they're doing it right.”

Ahmed said his team is looking to spread their AR technology and license it to other companies, targeting to conduct 1,000 neurosurgeries in 2025.

Advertise

Advertise